The shortest route from Europe to the USA goes via the North – Iceland – Greenland – Newfoundland. Nowadays, commercial airlines always fly direct without the need for a fuel stop. Until the 1970s, fuel stops were the norm and back then, large airports were built in North East Canada and Greenland as well as North West Scotland to refuel passenger airplanes. Today these airports mostly serve as alternates in case of emergencies or for lowly private airplanes such as ours which do not have the fuel capacity to make it in one go. A TBM can fly from Iceland to Newfoundland in favorable winds but it really means stretching the range unless one installs an extra fuel tank in the cabin (for which our aircraft has an approved modification).

In addition to fuel stops, it is also important to sufficient alternate airports available in case a landing at the airport of destination is impossible. This could be due to a sudden change in weather (very common in the polar region) or a preceding aircraft having an accident and blocking the runway. Legally, crews are required to carry enough fuel to fly to their destination, then to an alternate airport and circle there for 45 minutes. If the alternate airport is very close, it is also more likely that it can suffer from the same weather deterioration as the destination and be of no help. If it is far away, a lot of extra fuel is required and the effective range of the aircraft becomes much smaller.

While Greeland has quite a few airports on its coastline, they are mostly very challenging and not all-weather capable. Greenland is a massive rock and with each airport you fly in high terrain on all sides. On top of that, there is no Air Traffic Control (ATC) using radar equipment to guide aircraft. Crews are completely on their own, relying on on-board navigation. Most airports have very high weather minima — meaning visibility and cloud bases have to be above a rather high threshold to be useable. With the typical fjord/canyon airport, you want to make sure you turn into the right canyon and don’t fly against a mountain once you turn around the corner. For each approach, the go-around has to be considered as well. At any point during the approach, there might be the need to abandon the approach, climb up to cruise and reposition for another approach or divert. This all needs very careful planning and high safety margins. Greenland is full of aircraft wrecks and keeps attracting more.

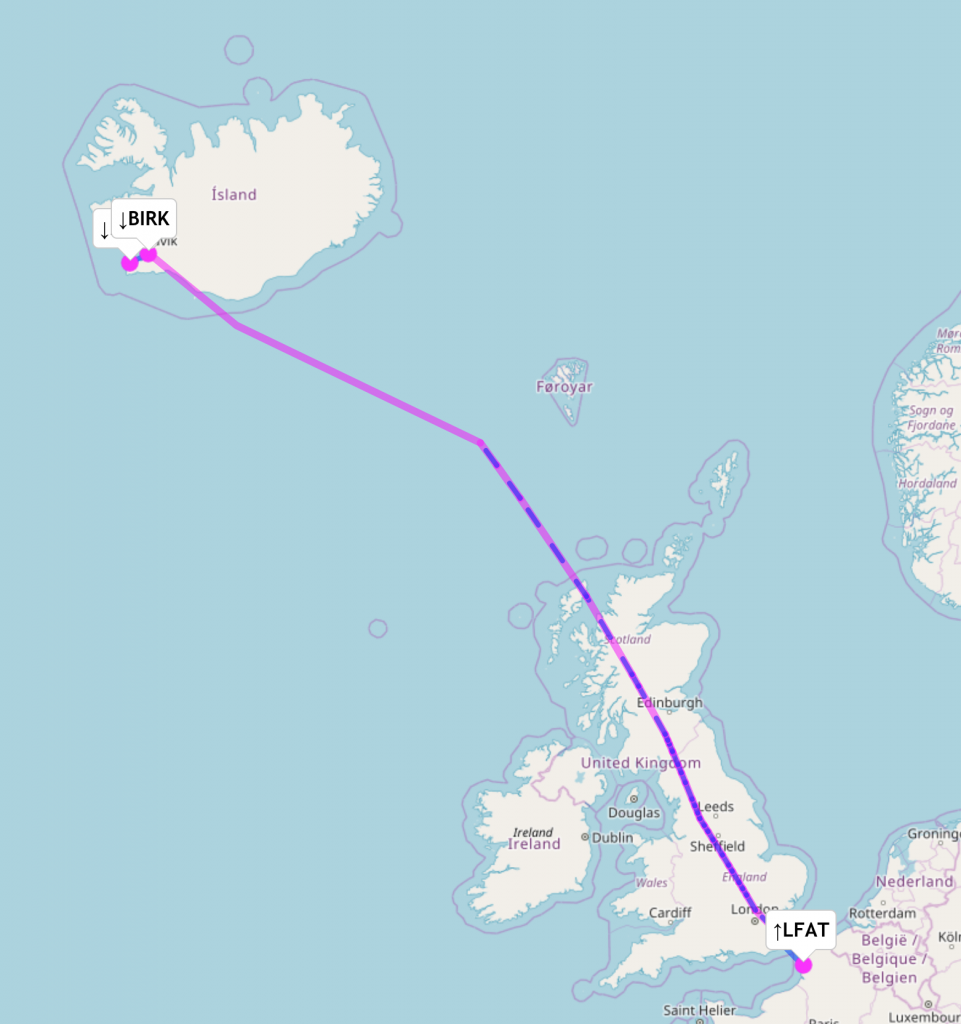

Le Touquet to Reykjavik

For the first Atlantic crossing, we decided to fly on the same day as a few other, experienced aircraft so that we can benefit from their assessment of the weather and situation and get some advice. The trip starts at Le Touquet / Paris Plage in France with a flight to Reykjavik/Iceland on Sunday July 22nd. Depending on how the winds turn out, an additional fuel stop in Scotland might be required.

Reykjavik is a fully equipped airport with everything we know from Europe. An even more capable airport — Kevlavik — is just around the corner and serves as the alternate. Should the headwind be too strong, a fuel stop in Wick, Scotland is planned. This flight should take between 4 and 5 hours, depending on winds. In Reykjavik, a visit to the Blue Lagoon is planned to prepare for the next day.

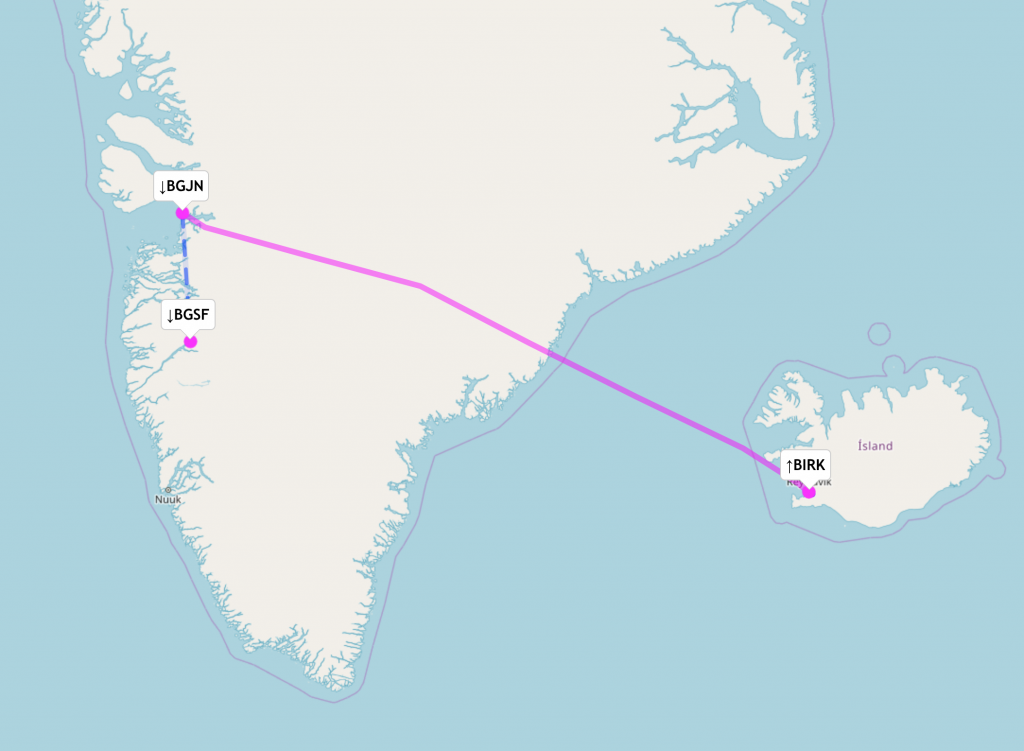

Reykjavik to Ilulissat

On the next day after the first weather reports and forecasts from Greenland arrive, we plan to depart to Ilulissat (formerly Jakobshavn) in Greenland.

The flight is expected to take about 3 hours. Ilulissat has an 845m runway with a 635ft/800ft minimum, depending on runway direction. This is rather challenging, also because it requires self-positioning from the enroute phase, i.e. pilots have to manage their own descent from cruise altitude while maintaining terrain and obstacle clearance and arriving at the approach point at exactly the right altitude. The airport chart also warns about something we’ve not had to deal with so far: “icebergs 790 feet”.

The alternate is 130 NM South and called Kangerlussuaq (formerly Sondrestrom). This is the best equipped airport of Greeland with a 2800m runway and a 350ft minimum. The downside is that it’s inside a fjord so make sure you got the approach well figured out and don’t take a left when you’re supposed to take a right — all while being inside clouds with strong turbulence, icing, etc. Sondrestrom is where Air France would land should it blow another engine but half an hour earlier than last time.

The goal for Ilulissat is to check out what kind of lunch is offered there, how freezing temperatures during the month of July feel like and whether European mosquito repellant is considered as such by Greeland mosquitoes.

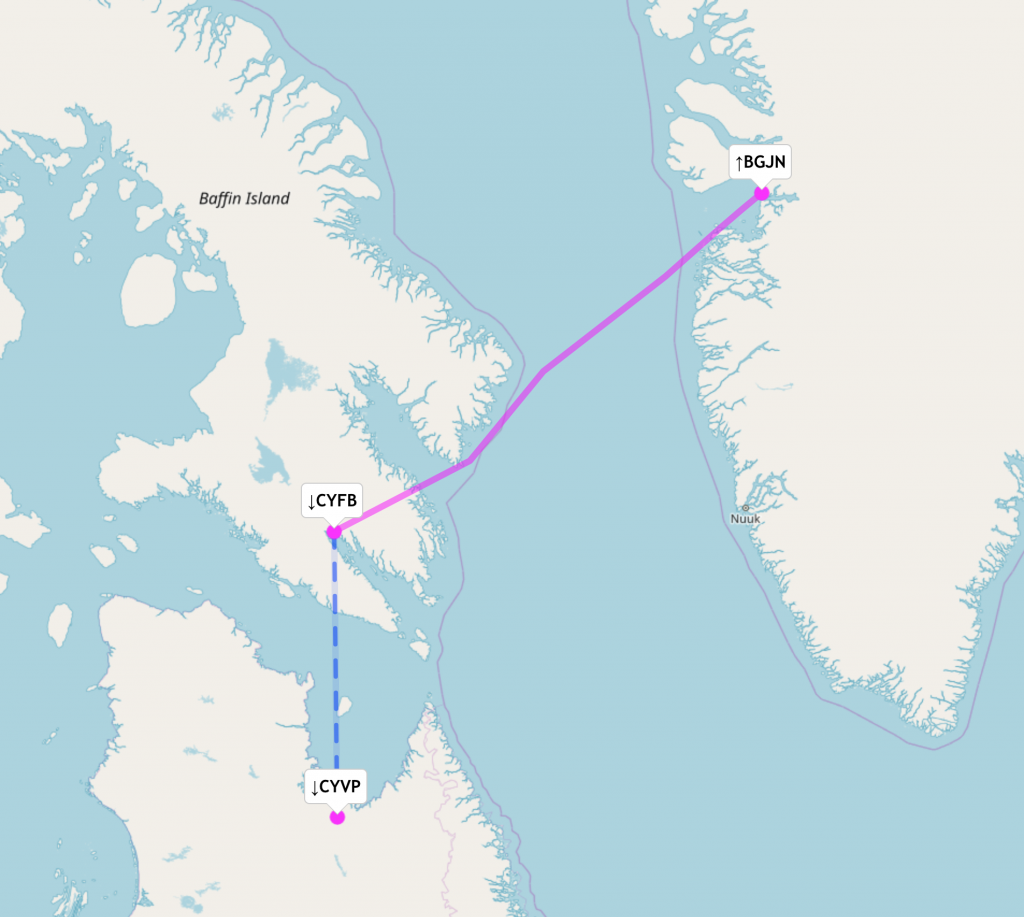

Ilulissat to Iqaluit

Iqaluit is better known as “Frobisher Bay” and probably even more remote than the previous places. It is located in Newfoundland and explains why the name Canada comes from German “keiner da” (nobody there).

Iqaluit is the final destination for Monday and last stop before the US of A. The airport is very well equipped with radar, long runways and approaches with good weather minima. The flight should only take 2 hours and as alternate, there are Kuujjuaq and Goose Bay which is the standard airport for small aircrafts taking the route via the Southern tip of Greenland.

The next day then brings two more flights: an immigration stop in Michigan and the approach to Oshkosh.